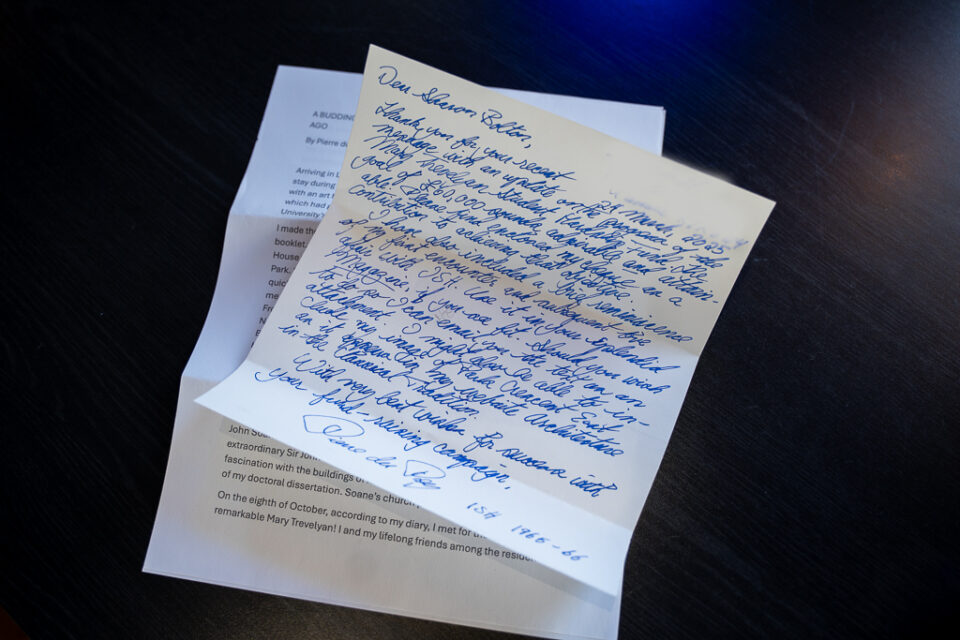

By Pierre du Prey (Resident at ISH 1965-66)

Arriving in London on the 28th of June 1965, my first task was to find a place to stay during the forthcoming academic year. I had graduated earlier that month with an art history undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, which had given me a Thouron Award with which to study at London University’s Courtauld Institute of Art.

I made the rounds of the various student residences listed in an out-of-date booklet. But I soon heard through the grapevine that International Students House was about to open an as-yet-unlisted “hostel” in the area of Regent’s Park. So, I headed up Portland Place full of anticipation – anticipation that quickly turned into sheer delight. Chris Paton and Bill Murray warmly greeted me, I recall, but in addition to that the building itself appealed to me greatly. From art history textbooks, I knew that in the early nineteenth century, John Nash had designed a row of elegant private houses called Park Crescent. Badly bomb-damaged in World War II, then finally restored, one curving end had just been transformed into spanking new housing for the likes of me, a foreign student on a limited budget. It was love at first sight on my part, and fortunately, I managed to secure one of the few remaining rooms.

As it happened, my room at ISH occupied the top floor. I overlooked the courtyard in the foreground and, across busy Marylebone Road in the background, stood Holy Trinity Church, by Nash’s great rival, the architect Sir John Soane. And, as luck would have it, during that autumn I discovered the extraordinary Sir John Soane’s Museum, which launched me on a lifelong fascination with the buildings of its owner/designer, subsequently the subject of my doctoral dissertation. Soane’s church provided my daily wakeup call.

On the eighth of October, according to my diary, I met for the first time the remarkable Mary Trevelyan!

I and my lifelong friends among the residents and non-residents at ISH, attended her unforgettable Goats Club meetings, at which she would invariably pull out of her conjurer’s top hat some leading light from the worlds of politics or the arts. Those were heady days, when it really seemed that London’s cultural scene lay open to us students like a bottomless treasure chest.

Turn the clock forward to 1978. By this time, I had married Julia and was the proud parent of a baby boy, Nicolas, born in Kingston, Ontario, where I taught art history at Queen’s University. My first sabbatical leave from there gave me the chance to turn my thesis into the first of my books on John Soane. We were delighted to renew old acquaintances at ISH and find accommodation for a couple of months in its splendid married students’ housing, located in Nash’s York Terrace East. Instead of busy Marylebone Road, the windows of our flat overlooked tranquil Regent’s Park – a good thing, too, because Nicolas went to bed early and slept like a top. But he also woke with the birds. I remember pulling aside the curtains by his cot so that he could look out on foggy autumn mornings when grey-cloaked, mounted Horse Guards would often ride by in formation only to disappear into the swirling mist.

Unforgettable.

I owe ISH so many good memories and fond friendships. Your 60th anniversary year puts me in mind of seeing for the first time those freshly painted colonnades and experiencing the welcome that lay behind them. I had to rub my eyes to believe that I might inhabit such a seeming palace; a palace moreover devoted to the concept of fostering international fellowship, a concept of importance as much now if not more so than in 1965.

Long live ISH and the principles for which it stands!